FRAM I Ice Station 1979

Location and Duration

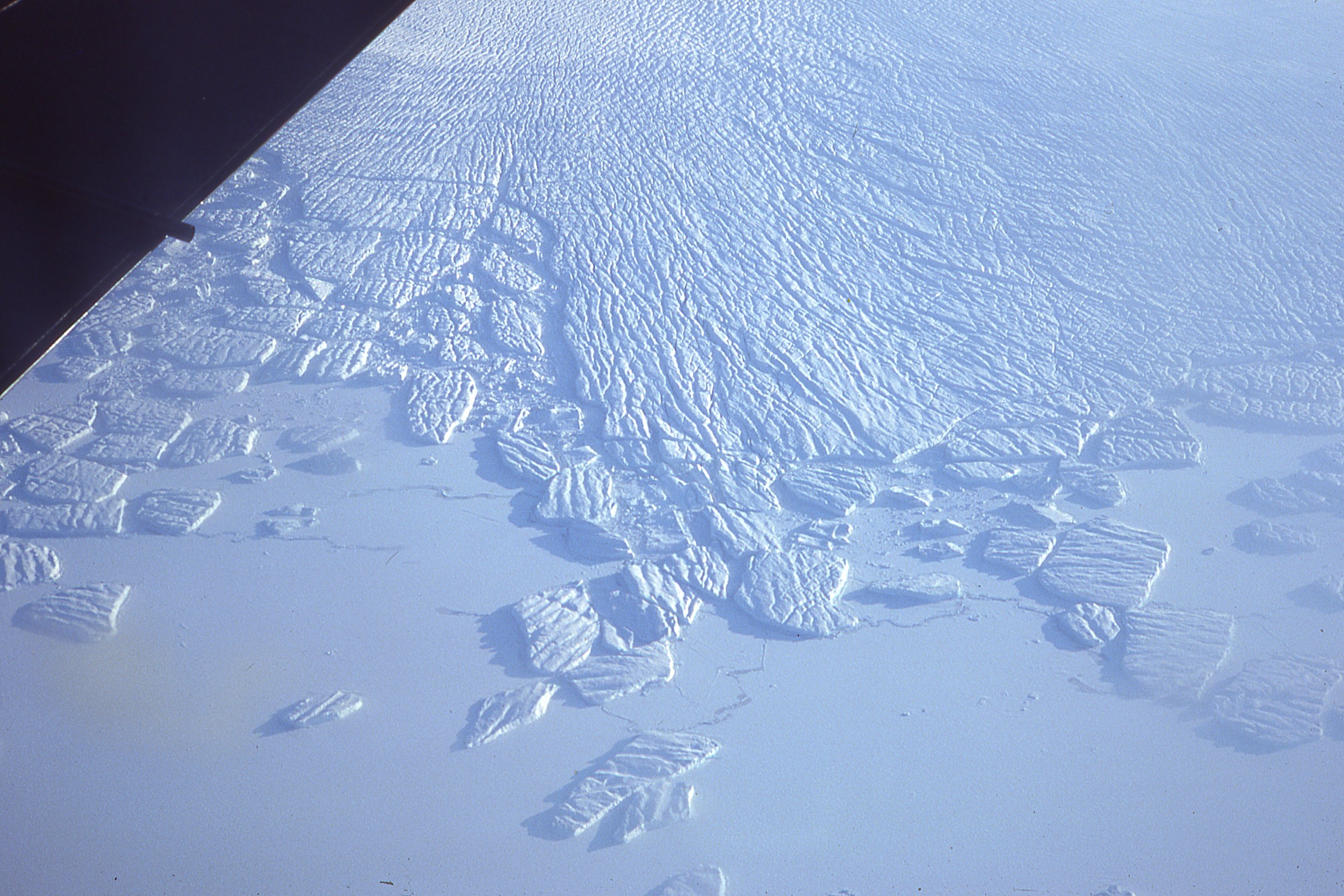

FRAM Helicopter CTD Survey

Central Arctic

15 Mar 1979 to 10 May 1979 (Representative photographs here)

Background

In 1978 we moved to Thetford, Vermont when I joined the Snow and Ice Branch at the US Army Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory. I had been recruited and found that I liked the culture and people there and felt that I immediately fit in. Before leaving Seattle, as AIDJEX was transitioning to the Polar Science Center as part of the Applied Physics Lab, I had been awarded a grant to study inertial oscillations, and had also developed a keen interest in understanding what maintained the Arctic halocline, a cold relatively saline layer that over most of the Arctic Ocean separates cold and fresh surface layer from the underlying warm water of Atlantic origin. This was a critical aspect of what maintained the thick perennial Arctic ice pack. I was intrigued with a highly portable profiling conductivity/temperature/depth (CTD instrument that had been developed at APL and used by J. Garrison to sample over the continental shelf off Bering Strait. About that time I lost some of my naiveté of science and scientists. I was told, for example, by a respected UW professor that an idea I had for a novel sampling program in the Arctic was impractical, almost laughably so. I learned that within days he had submitted a letter proposal to ONR and would receive funding for exactly that work. That made for an amusing anecdote, but another event during my last year in Seattle was less comical. Word had gone out from ONR that there would be a series of ice stations in the eastern Arctic over the next few years. The first, FRAM I, scheduled for spring of 1979 would emphasize geophysics, which would entail helicopter support. I saw an opportunity for using a portable CTD system to piggyback on the helo operations and learn much new about the upper ocean in that region. I sent a letter to ONR outlining the work. Andy Heiberg attended an early planning meeting for FRAM I also attended by Ken Hunkins, a professor at Lamont-Doherty, who apparently put forward a proposal quite similar to mine. Andy reminded those present of my letter, which would probably not have been discussed otherwise. The rather odd upshot was that I was co-funded with Hunkins to do the work, but rather than use the APL instrument that I recommended and had been used previously in the Arctic, Hunkins was to contract development of a new portable CTD. Hunkins and I had had previous differences. I thought he had been chosen improperly over Jim Smith to manage the oceanography program for the year-long AIDJEX Main Experiment. My responsibility for the ocean aspect of the AIDJEX modeling effort required analyzing the ocean measurements, which I found to have serious defects. I suspect Hunkins resented my interference, and by the time of FRAM our relations were somewhat strained. Although I had received a grant from ONR for the work, during the project he pointedly excluded me from PI meetings.

As it turned out, obtaining the ODEC instrument Hunkins promised was not seamless. Delivery was delayed until the very last minute, in fact, it arrived at CRREL late in the afternoon before I was scheduled to fly down to McGuire AFB to get the military flight to Thule. Instead of being packed in two separate boxes as promised, the instrument arrived in one box that exceeded the airline dimensions for excess baggage. It would not fit in the commuter flight from Lebanon to Boston, so Saundie had to drive me to Logan, where after much pleading, I managed to get it on the flight to Philadelphia (airlines were a little more accomodating back then). Then it was a significant hassle to get it and me out to the air force base, where again I had to plead with the MAC personnel to put in on the C-141 flight to Greenland. Exhausting day. We left late in the evening, stopped for some time at Goose Bay, Newfoundland, to refuel, and finally made Thule the next afternoon. Although it got off to a rocky start, FRAM I became an unforgettable and rewarding adventure for me.

Thule was an adventure in itself. I had expected to fly out to Station

Nord, an emergency airfield at the northeast tip of Greenland, and from

there by Twin Otter out to the ice camp, which by now had been

established. The flight out to Nord would be in the Tri-Turbo 3, an

aircraft based on a C-47 airframe to which three turboprop engines were

affixed.

I learned on arrival that the flight to Nord would be delayed

because of weather, so I settled in for the night in an empty barracks,

and eventually wandered over to the officers' club, where I met up with

the Tri-Turbo pilot, a crusty guy named Dickerson (never learned his

first name) and the co-pilot, "Fish" Salmon.

As it turned out, we a spent nearly a week waiting for decent flying

weather to happen at both Thule and Nord, and I got to spend a fair amount

of time with the pilots. In one memorable conversation, after finding out

my main science interest was turbulence, Fish allowed that during his time

as the lead test pilot for Lockheed after the war (which of course got my

attention) fellow test pilots had been lost pulling out of dives after

they had gone supersonic. As he put it, he took a group down to CalTech to

talk to a professor there, he couldn't remember his name, who diagrammed

on the chalk board what was happening. He said it all made sense. I

ventured a guess,"Von Karman?" "Yeah, that's the guy." I couldn't believe

it, here, in the officers club in Thule, Greenland, I was talking to

someone who thirty years earlier had been at the very forefront of

aviation, and had been advised by none other than Theodor Von Karman, a

giant in the field of turbulence theory.

I learned on arrival that the flight to Nord would be delayed

because of weather, so I settled in for the night in an empty barracks,

and eventually wandered over to the officers' club, where I met up with

the Tri-Turbo pilot, a crusty guy named Dickerson (never learned his

first name) and the co-pilot, "Fish" Salmon.

As it turned out, we a spent nearly a week waiting for decent flying

weather to happen at both Thule and Nord, and I got to spend a fair amount

of time with the pilots. In one memorable conversation, after finding out

my main science interest was turbulence, Fish allowed that during his time

as the lead test pilot for Lockheed after the war (which of course got my

attention) fellow test pilots had been lost pulling out of dives after

they had gone supersonic. As he put it, he took a group down to CalTech to

talk to a professor there, he couldn't remember his name, who diagrammed

on the chalk board what was happening. He said it all made sense. I

ventured a guess,"Von Karman?" "Yeah, that's the guy." I couldn't believe

it, here, in the officers club in Thule, Greenland, I was talking to

someone who thirty years earlier had been at the very forefront of

aviation, and had been advised by none other than Theodor Von Karman, a

giant in the field of turbulence theory.

Another memorable item during that week in Thule was the occurrence of a "Phase IV" weather event, a katabatic wind storm that comes off the Greenland ice cap, with hurricane force speeds. During them the whole base shuts down and everyone was confined to quarters. I was alone for two full days in a barracks that would have housed at least two dozen, hearing the high-pitched howl of the wind, looking out on horizontal blowing snow in the lights of a truck that had been left running, and eating stockpiled MREs. Finally the wind died and we all emerged. I learned that a British fighter squadron head flown in just ahead of the storm with barely time to park their aircraft in one of the huge hangers. Unfortunately, instead of completely closing the hanger door, they had left a small gap near the floor. The upshot was that the hanger completely filled with fine-grained snow, and there were apparently some choice words between the Air Force NCOs and the British fighter crews.

At last the weather cleared, we loaded the Tri-Turbo with gear and took

off for Station Nord with me as the only passenger. The aircraft was not

pressurized,

which meant we could not fly directly over the two-mile thick ice cap

but had to instead hug the north coast. For me this meant observing

probably the most scenic flight one can imagine. My view was aided by

large picture windows in the main cabin, which I had been told were

installed in hopes of fostering

which meant we could not fly directly over the two-mile thick ice cap

but had to instead hug the north coast. For me this meant observing

probably the most scenic flight one can imagine. My view was aided by

large picture windows in the main cabin, which I had been told were

installed in hopes of fostering

sales to the air forces of African countries. The Tri-Turbo was the

brainchild of Beau Buck, whos company out of Santa Barbara did a lot of

work, classified and not, for ONR. Beau was a colorful character, with a

slight taint of "beltway bandit," who was famous in the polar community

for starting talks with the statement: "Arctic experts are those who have

been there twice, or those who have been there N times," where of course N

was the number of time he had been there. His point was well taken,

especially by me, who had been there about twice, and had a whole lot to

learn.

sales to the air forces of African countries. The Tri-Turbo was the

brainchild of Beau Buck, whos company out of Santa Barbara did a lot of

work, classified and not, for ONR. Beau was a colorful character, with a

slight taint of "beltway bandit," who was famous in the polar community

for starting talks with the statement: "Arctic experts are those who have

been there twice, or those who have been there N times," where of course N

was the number of time he had been there. His point was well taken,

especially by me, who had been there about twice, and had a whole lot to

learn.

The Experiment

After spending a night at Station Nord, we loaded the Twin Otter and took

off for the FRAM ice camp, arriving just in time to watch a C-130 air drop

our fuel supplies. The personnel on the surface directing the drop assured

us they were experienced. Nevertheless, for a few tense moments it looked

like the pallets, each with four drums of aviation fuel, were headed right

at us. Turned out they were right on target.

The Air Force guys went out to salvage parachutes, but left behind

the

shrouds. I noticed that Allan Gill was following them out collecting the

nylon shroud lines. I followed him, for little is more valuable in a

project than having a plentiful supply of light, strong lines to fix

whatever needs fixing. Following Allan set the pattern for me for all of

FRAM: I soon figured out that if I wanted to thrive in that environment, I

should watch him closely and try to do whatever it was that he did.

The Air Force guys went out to salvage parachutes, but left behind

the

shrouds. I noticed that Allan Gill was following them out collecting the

nylon shroud lines. I followed him, for little is more valuable in a

project than having a plentiful supply of light, strong lines to fix

whatever needs fixing. Following Allan set the pattern for me for all of

FRAM: I soon figured out that if I wanted to thrive in that environment, I

should watch him closely and try to do whatever it was that he did.

There was good reason for emulating Allan. He had been part of the

four-person British Transarctic Expedition led by Wally Herbert

that sledged from Alaska to Svalbard for 16 months, starting

in Feb, 1968. They reached the North Pole in Apr, 1969, having got there

via the "pole of innaccessibility." In all respects it was a remarkable

journey, and as more and more questions have surfaced about Peary's

account, it was probably the first time men reached the North Pole by

surface travel. Allan didn't talk a great deal about it, but one time he

did describe crossing the shear zone north of Alaska near the start of

their journey, traveling at night. Although delivered in his typical

low-key style, the description was dramatic and terrifying. At the time I

had recently seen radar video of giant pressure ridges moving along the

coast off Barrow, and found it hard to imagine taking a dog sledge through

that zone. Another time, he talked of running out of food on an attempt

with Herbert to circumnavigate Greenland, and becoming hungry to the point

of starving. They managed to shoot a walrus, and he said that although

normally he considered walrus almost unfit for human consumption, on that

occasion nothing had ever tasted better! I remember thinking I had never

been really hungry a day in my life. At a more mundane level, I observed

and then copied the way Allan donned clothes by adding layer after layer.

I also noticed that when outside he never moved slowly. It didn't take

long to realize that if you walked somewhere fast you got there a lot

faster and a lot warmer. Sounds obvious, but I have often noticed

that when people first encounter a new environment, they tend to slow

everything down. At any rate, within the first two weeks of my first solo

Artic project, I had met a famous test pilot who had got advice from Von

Karman, and begun working with a true Arctic explorer, who turned out to

be both a mentor and friend.

that sledged from Alaska to Svalbard for 16 months, starting

in Feb, 1968. They reached the North Pole in Apr, 1969, having got there

via the "pole of innaccessibility." In all respects it was a remarkable

journey, and as more and more questions have surfaced about Peary's

account, it was probably the first time men reached the North Pole by

surface travel. Allan didn't talk a great deal about it, but one time he

did describe crossing the shear zone north of Alaska near the start of

their journey, traveling at night. Although delivered in his typical

low-key style, the description was dramatic and terrifying. At the time I

had recently seen radar video of giant pressure ridges moving along the

coast off Barrow, and found it hard to imagine taking a dog sledge through

that zone. Another time, he talked of running out of food on an attempt

with Herbert to circumnavigate Greenland, and becoming hungry to the point

of starving. They managed to shoot a walrus, and he said that although

normally he considered walrus almost unfit for human consumption, on that

occasion nothing had ever tasted better! I remember thinking I had never

been really hungry a day in my life. At a more mundane level, I observed

and then copied the way Allan donned clothes by adding layer after layer.

I also noticed that when outside he never moved slowly. It didn't take

long to realize that if you walked somewhere fast you got there a lot

faster and a lot warmer. Sounds obvious, but I have often noticed

that when people first encounter a new environment, they tend to slow

everything down. At any rate, within the first two weeks of my first solo

Artic project, I had met a famous test pilot who had got advice from Von

Karman, and begun working with a true Arctic explorer, who turned out to

be both a mentor and friend.

It didn't take long to settle into a routine at the camp. It turned out

the geophysics team, led by Yngve Kristofferson, had problems with

instruments to be deployed at remote locations. Their problem was our good

fortune, because it increased helicopter time for our program. The region

in which FRAM I drifted, an area bounded by 83º to 85ºN, 006º to 011ºW,

was of special interest because (a) very little previous data were

available; (b) it was where cold, relatively fresh water of the Transpolar

Drift Stream interacts with warmer, more saline Atlantic water flowing

north through Fram Strait, (c) the overall stability of the water column

was less than in the western and central Arctic, and (d) there was thought

to be large variation in near surface properties on relatively short

horizontal scales. I divided the sampling program into a large scale

survey, comprising linear transects of 7 stations spanning about 300 km,

centered on the drift station, and a more closely spaced small scale

survey where the largest change in properties was found.

We used the portable self-contained CTD instrument (ODEC Model 202)

lowered by Kevlar cable to depths of about 280 m. For a typical station

we would

fly to the target location, look for an ice edge with access to open water

or thin ice, then drop the probe and reel it back in with a small electric

winch.

After each station we could do a quick check of the recording and

use the data in some cases to plan the next station, particularly during

the small-scale survey. A typical large-scale transect would take a day,

with three stations out to 150 km in the morning, return to camp for

lunch and to recharge the ODEC batteries, then do three more stations in

the opposite direction, finishing with a station at the camp to compare

with the Plessy oceanographic CTD stationed there.

After each station we could do a quick check of the recording and

use the data in some cases to plan the next station, particularly during

the small-scale survey. A typical large-scale transect would take a day,

with three stations out to 150 km in the morning, return to camp for

lunch and to recharge the ODEC batteries, then do three more stations in

the opposite direction, finishing with a station at the camp to compare

with the Plessy oceanographic CTD stationed there.

I remember FRAM I as being cold, day after day of cold wind from straight across the North Pole and temperatures in the -30 to -40ºC range. I had a side project collaborating with Norbert Untersteiner, where I used arrays of frozen-in thermocouples and ice thickness gauges to monitor temperature gradients and growth (or ablation) at the ice base. They were deployed some distance from the main camp, and I would daily haul a generator and voltmeter out to the site to make the measurements. At first I used one of the camp snowmobiles, but after a few days realized that skiing would keep me a lot warmer, as well as providing exercise. Generally there was plenty of heat in the huts, but one exception was the sleeping hut I shared with 3 or 4 other men. The problem was that Ken Hunkins' grad student had to make a CTD profile every morning at 4 am. We would hear his alarm and usually a few choice words as he rushed to keep the schedule. For several mornings in a row, he would leave the door open, and by time to get up for breakfast, the temperature in our hut would be well below zero. Finally, someone threw a boot at him as he was leaving, telling him to "shut the damn door," and the problem resolved itself. One exception to the cold was Easter Sunday, when the wind stopped, the temperature rose to around -20 ºC and we were sitting out in shirtsleeves!

Allan and I did most of the helicopter CTD sampling. For a typical

station we would land beside open water or near thin ice, and set up the

winch with its

derrick, start the generator. We would then let the instrument drop to its

maximum depth, typically 270 m, and begin reeling it back with the powered

winch. A station typically took 45 min to an hour, which meant standing

pretty much still for that time, and it sometimes did get pretty cold.

Most oceanographic winches have a "level wind" that shuttles back and

forth so that the cable winds uniformly on the spool as it is pulled in.

We had no such

luxury, and in order to prevent overlaps and binding, we would guide the

cable back and forth with our gloves. Allan and I would trade off as level

winders, and at some point it became a contest to see who could wind the

cable with the fewest overlaps, with whoever was not winding being the

judge. Another lesson about working in the polar

environment: by making something that was otherwise tedious a

contest, time passed quickly and if you were concentrating on making the

"perfect" level

wind (something accomplished just once, by Allan of course) the cold was

easily forgotten. Pretty soon Helge and Jøran, who had often remained in

the helicopter, were asking for turns, a bit reminiscent of how Tom Sawyer

got the fence whitewashed.

environment: by making something that was otherwise tedious a

contest, time passed quickly and if you were concentrating on making the

"perfect" level

wind (something accomplished just once, by Allan of course) the cold was

easily forgotten. Pretty soon Helge and Jøran, who had often remained in

the helicopter, were asking for turns, a bit reminiscent of how Tom Sawyer

got the fence whitewashed.

On one occasion, we received a radio call from camp asking us to return, because a sizable crack had split the camp. As we flew in we could see people moving equipment from a hut cantilevered over the edge. After things had settled a bit, I started to assemble the portable CTD equipment at the edge, thinking this would be a good opportunity to get a time series where there was rapid freezing (something that became the focus a later (LEADEX) project). For some reason, Hunkins more or less ordered me to stop-- he was still chief scientist although he would leave in a few days. For me it was just another in a series of snubs and criticisms, a continuation of differences dating from AIDJEX. The crack continued to widen, eventually it would become several hundred meters wide and would freeze thick enough to be the new runway. I heard later that our cook, a young woman who was good at her job and well liked, heard the noise outside, went to open the messhall door, looked down on 4,000 meters of water about a foot away, sat down on the floor, and started crying. She was good natured about the inevitable ribbing.

Sometimes a safe landing spot would be a ways from where we could deploy the instrument, and we would have to make our way through broken up rubble. Allan would lead and I would follow with the instrument on my shoulder, literally walking in each of his footsteps. Nevertheless, twice I went in up to my hips where he hadn't. Fortunately, Jøran carried an extra pair of wind pants, and we would go on to the next station. The whole camp started referring to Allan's ragged old mukluks as "Jesus boots."

There were other lessons that had to be learned the hard way. Helge and Jøran had set up a platform on top of fuel barrels where they parked and covered the helo every evening. One day we returned from one of the long survey lines, and Helge brought the aircraft down to just above the landing, but remained in a hover a foot or two above the platform. After a while, Jøran motioned for us to open the door and get out, which we did and headed for the messhall for coffee. Sometime later we heard the helicopter shut down, and soon they joined us. As they told it, the problem had been that meltwater from small amounts of snow we had brought into the cabin on the winch and instrument at each station dripped below the cabin and had eventually frozen the throttle cable, so they had no way of shutting off the engine except by running it out of fuel. Needless to say we were more careful from then on. We spent a lot of time flying, and I developed deep trust in the helo crew. They were interesting people and besides being very good at what they did, added greatly to the social aspects of the camp. At one point in the two month long camp, Helge was relieved for a week by a replacement, whom we were told was a Swedish fighter pilot. By then Allan and I had got pretty blase about buckling up, but on the first flight with the new pilot we discovered that he liked to skim the surface, then rise abruptly to clear each pressure ridge. After the first ridge, without looking at each other Allan and I reached for our seat belts simultaneously, then laughed about it. I remember on one flight being quite worried because on that day Saundie and our three girls were flying west to Yakima to take a break from the collective concern in the Northeast over the nuclear accident at Three Mile Island. Yet it did occur to me that the risk of being in a helicopter over the Arctic ice pack, a long way from rescue, was actually greater than that they faced in a commercial airliner.

One of the really memorable aspects of FRAM was that late Saturday

evening, after all the science for the week had been wrapped up, the entire

crew would gather in the messhall to socialize. Gøran would bring his

coveted sound system, music would play (BGs Saturday Night Fever was a

favorite), people would relax, drinks would

appear, and pretty soon a good party was underway. Sometime in the

wee hours, Yngve Kristofferson would disappear for a while but would

return shortly with

an elf-like smile. Inevitably, someone would have to answer a nature call,

and then we would hear explosions and usually some choice expletives just

outside the messhall. Turns out that Yngve had rigged trip wires for

pyrotechnics intended as polar bear warning to catch whoever came out

first. Bears were scarce during FRAM. In fact, toward the end of the

project two bear experts from the University of Montana came out to

continue an ongoing study of polar bears. When they could, they would ride

with us on our survey legs, hoping to spot a bear, dart it from the helo

and study its vitals. We never saw one, and they decided to give up and

accompany me back to Station Nord at the end of my project. When we landed

there, we heard that a bear had indeed shown up at camp soon after we

left.

appear, and pretty soon a good party was underway. Sometime in the

wee hours, Yngve Kristofferson would disappear for a while but would

return shortly with

an elf-like smile. Inevitably, someone would have to answer a nature call,

and then we would hear explosions and usually some choice expletives just

outside the messhall. Turns out that Yngve had rigged trip wires for

pyrotechnics intended as polar bear warning to catch whoever came out

first. Bears were scarce during FRAM. In fact, toward the end of the

project two bear experts from the University of Montana came out to

continue an ongoing study of polar bears. When they could, they would ride

with us on our survey legs, hoping to spot a bear, dart it from the helo

and study its vitals. We never saw one, and they decided to give up and

accompany me back to Station Nord at the end of my project. When we landed

there, we heard that a bear had indeed shown up at camp soon after we

left.

As we filled in the large scale array, it became clear that there was a fairly pronounced change in near surface ocean properties across our array, so I designed a smaller scale array that would delineate where and how concentrated was the boundary between the water masses. The more closely spaced array illustrated that the boundary was a relatively narrow front separating a more saline, slightly colder surface layer to the southeast from its counterpart to the norhtwest. As we narrowed the search, it became clear that the camp itself was nearing the frontal zone, and soon drifted directly across it. Near the center of the front, data from a profiling current meter showed a unidirectional current between approximately 20 to 70 m depth. I mobilized the helo crew to rapidly sample at short spacing across the front. We were able to document a 25 km wide front where denser water was displacing lighter, and where rotation (Coriolis force) played a major role. I surmised that we were sampling at the leading edge of the annual Arctic halocline replenishment from cold, saline water produced on the Siberian shelves.

FRAM I was a truly valuable learning experience for me, and most importantly, gave me confidence that I could plan and execute a scientific program that yielded important new understanding of a geophysical system. I returned to Vermont for a wonderful homecoming with the family I had been missing sorely for two months.

McPhee, M. G. and N. Untersteiner. 1982. Using sea ice to measure vertical heat flux in the ocean , J. Geophys. Res., 87 (C3), 2071-2074.

McPhee, M. G., 1986. The upper ocean. In: The Geophysics of Sea Ice, ed. N. Untersteiner, 339-394, Plenum Press, New York.